Formation Through Fracture

- Elizabeth Kim

- Dec 21, 2020

- 5 min read

"I am a product of two dissimilar narratives, and I find strain between a tension to investigate the validity of Biblical, historical, and archeologic accounts and a desire to simply trust."

Jesus’ sacrificial and victorious death on the cross fulfilled prophecy because not one of his bones was broken (John 19:36). However, for non-Jesus humans, fractures can be an unfortunate and frequent occurrence. During a medical school lecture about orthopedics, a physician showed our class the stress-strain curve of bone. He taught about the relationship between different types of force the bone may experience and the fracture patterns that result. If a bone is compressed, for example, after a jump from a tall building, the bone typically fractures in an oblique line. If rotational force is applied, a spiral fracture occurs. Depending on the rate a force is applied, our bone has a remarkable ability to undergo an elastic phase and respond to stress by changing its shape. This deformation may regress if the stress is removed in a short time, or the deformation may remain a unique feature of an individual’s skeleton if a bone is pushed for too long. Recollections about the effect of stress on the bone from this introductory orthopedics lecture served as a helpful image during a trip to Israel with fellow members of the Anselm House community. As we encountered God’s presence at different times during the journey, I was reminded that tension and stress are not always comfortable, but God uses them to shape our unique stories and teach us ways to better worship Him.

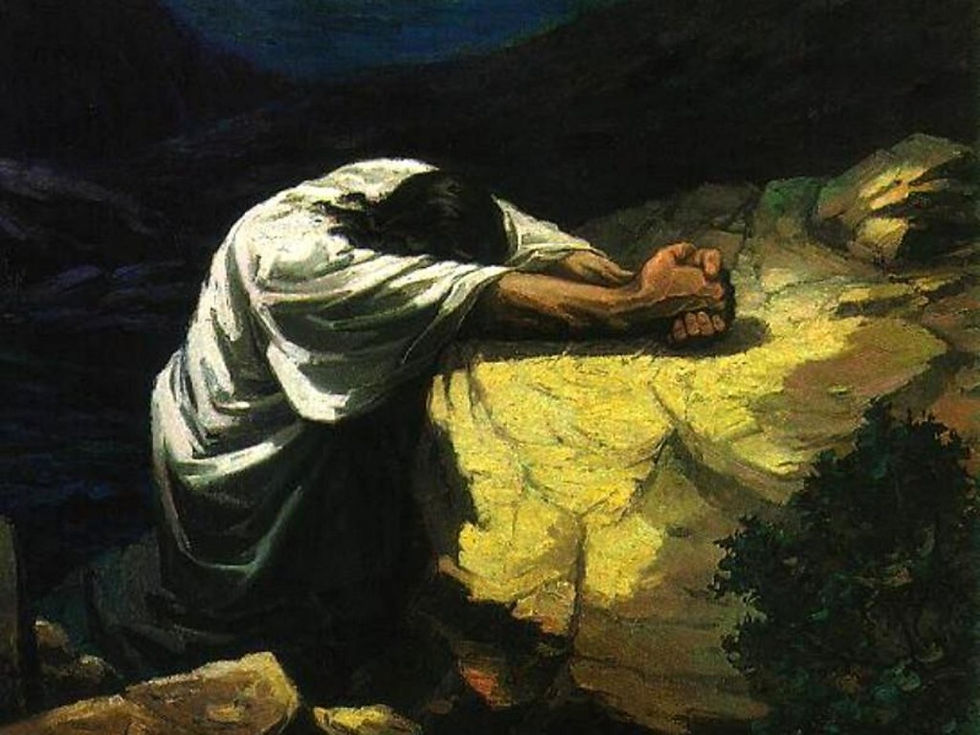

While Jesus was immersed in an environment that was filled with external tensions between North and South, Jews and Romans, Pharisees and Sadducees, I imagine that one of the moments He experienced the most internal conflict occurred while He was praying in the Garden of Gethsemane. As He communed with His Heavenly Father, He recognized the necessity of what was to come, yet asked for the cup to be taken from Him. Although this tension produced anguish, Jesus was able to respond by saying “not my will, but yours be done” (Luke 22: 39-44). As our group sat in the Garden of Gethsemane, we were able to reverently ponder the weight of the tension Jesus bore for us. In this time of reflection, a piece of internal conflict the Lord has placed in my story came to mind. My father is from South Korea. He was raised in Chicago, trained as a scientist, is a practicing physician, and values empirical evidence. He continues to wrestle with feeling connected to and loved by an entity that he cannot touch, see, or quantify. My mother was a nurse. She is Dutch and was raised in a South Dakota town with a population of 300. From her youth, she was an active member of a church community that reminded her of the importance of childlike faith. She is comfortable sitting in the Savior’s presence without the need for logical explanations or tangible proofs. I am a product of two dissimilar narratives, and I find strain between a tension to investigate the validity of Biblical, historical, and archeologic accounts and a desire to simply trust.

While sitting in the Garden, I could imagine the figurative stresses of my parents’ differing narratives pulling on my bones as I continued to process the recent death of a family friend. This humble, dedicated servant of Christ died at a young age of cancer. As greedy, malignant cells began to infiltrate different areas of her body, she became weaker, and I watched my parents’ different approaches to her prognosis. Dad advocated for the best medical treatment available, while mom turned to fervent prayer and fasting. I admired my parents shared efforts of supporting our friend and her family, but as I sat in the garden, I was upset. Both narratives seemed to fail. I could not understand God’s purpose for this loss and felt the weight of fracture and brokenness. In these feelings of disappointment, I revisited words shared during the funeral ceremony. We prayed to be strengthened to run the race for our righteous judge and to trust that God works for our ultimate good. We were reminded our friend’s life was a testimony that God is a good God even when we don’t understand the way He is working. With her in mind, I wonder if these moments in the garden were catalysts for the slow healing of a fracture and the formation of a fortified perspective of worship.

After our time in the Garden, our group transitioned across the road, and our guide introduced us to the Church of All Nations. He informed us of the tradition that the rock where Jesus prayed before His arrest is located inside. We were impressed by the beautiful outer façade of the church, and as we entered in silence, we tried to appreciate the intricate designs, the flags of several countries, and the symbolism of the dark, solemn environment within. I saw a group was praying, and as we approached the front of the church, I noticed something familiar. While my father does not speak much Korean, he has taught my sisters and I a few words: one of which is 고맙습니다 (Kamsahamnida), which means “thank you”. This word was repeated as the group continued to pray, and I was amazed at the way God was able to address a component of tension I have faced. We were standing in a church, a setting that has been extremely special to my mom throughout her life, and of all the times when our group could have entered the Church of All Nations, we visited while followers of Christ were participating in a communal prayer in my dad’s native tongue. I felt a wave of shalom—of peace, harmony, and wholeness—as I stood and was simply able to say thank you and 고맙습니다 to God. Areas of strain, fracture, and brokenness can be reformed by God to become points of stability. He can use stress and tension to strengthen us as we run the race. In this meaningful part of the trip to Israel, I learned to say thank you even when I don’t understand what God is doing, and I learned to choose to worship Him when times are simultaneously joyful and sorrowful.

Like our dynamic bones, tension shapes our spiritual journeys and our identities in Christ. While there will not be easy solutions to complex problems, and we may continue to have questions and doubts, there is beauty in being able to praise and thank God in the midst of the different internal and external stressors we may face. Through compression, bending, or spiral forces, may we continue to strive to worship the Lord with gratitude and a response of, “not my will, but yours be done”.

Comentarios